In their quest for better ways to heal the human body, healers throughout history have tried some strange methods and, by modern standards, often disturbing and unethical in treating diseases. One of the most disturbing is the practice of prescribing mummy powders for health.

However, not all mumia substances were the same. Sometimes the word referred to a resinous liquid supposedly filtered from corpses: the “concrete liqueur”.

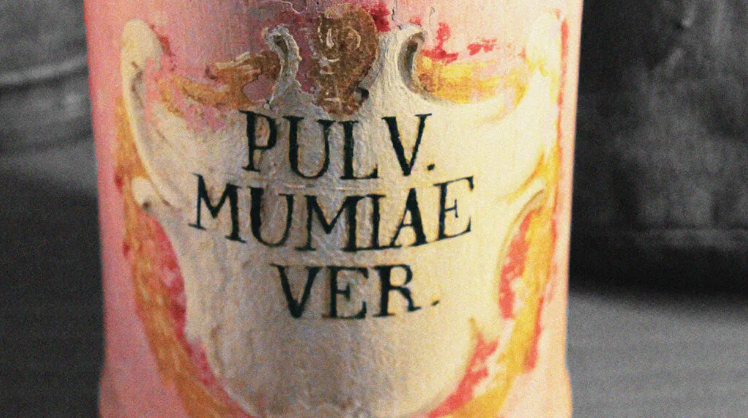

Other times he referred to “mummy dust,” finely crushed bones and other remains, or “a corpse tormented under the sand,” as he expresses in the treatise.

And in other cases, mumia referred to bitumen, a substance used by the ancient Egyptians in embalming, which Dr. James called “pissasphaltus”.

Noble also reports on Dr. Paré’s disapproval of such practices, highlighting his “condemnation of French apothecaries[…] who, in the absence of a superior mummy, were ‘sometimes moved … to steal at night the bodies of those who were hanged and embalmed with salt and in an oven, to sell them so adulterated instead of real mummy.”

Sugg, meanwhile, notes that “for a long time, accusations of cannibalism were used as an effective insult against the indigenous peoples of America and Australasia.” For centuries, however, Europeans had no qualms about consuming human remains for health, especially if those remains came from ancient graves in the Middle East.

Although this practice began to become extinct in the 18th century, Egyptian mummies remained at the center of intense European trade for another hundred years or so, as mummy brown, a pigment obtained from mummified remains, remained popular with Western painters. .

Finally, however, medicinal cannibalism went out of fashion altogether, partly thanks to the change in attitude towards human remains, which in the twentieth century had become decidedly less acceptable to the general public.

Some aspects of medical history may now seem shocking and repugnant, but keeping them in mind means taking into account societies’ changing attitudes toward good health and disease, and who can benefit from health care.

In the future, reflecting on these darker and more unusual sides of medical history can inform a more equitable and complete understanding of health practices.